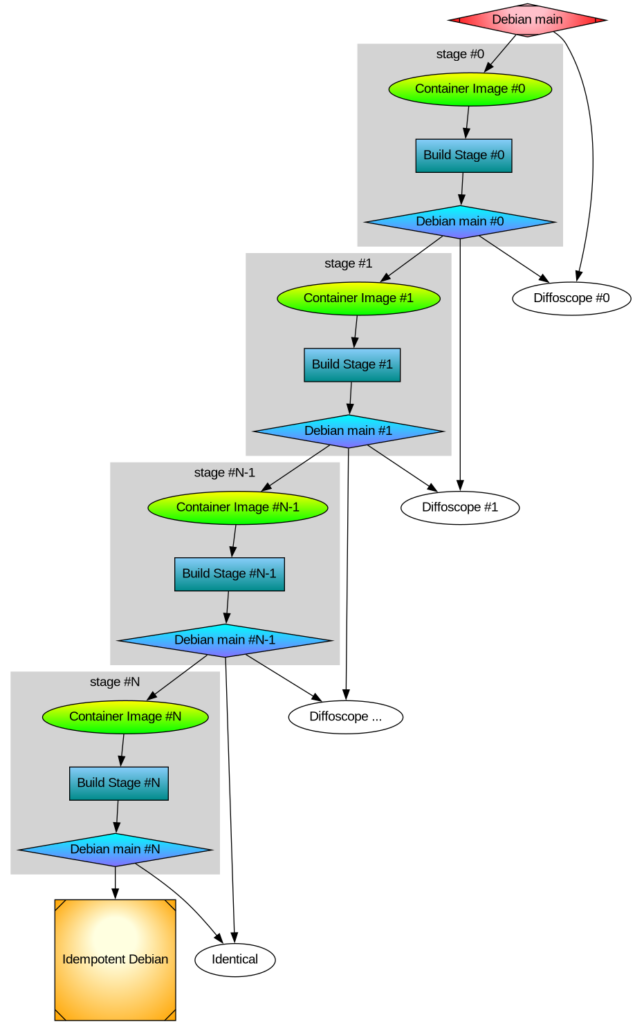

After thinking about multi-stage Debian rebuilds I wanted to implement the idea. Recall my illustration:

Earlier I rebuilt all packages that make up the difference between Ubuntu and Trisquel. It turned out to be a 42% bit-by-bit identical similarity. To check the generality of my approach, I rebuilt the difference between Debian and Devuan too. That was the debdistreproduce project. It “only” had to orchestrate building up to around 500 packages for each distribution and per architecture.

Differential reproducible rebuilds doesn’t give you the full picture: it ignore the shared package between the distribution, which make up over 90% of the packages. So I felt a desire to do full archive rebuilds. The motivation is that in order to trust Trisquel binary packages, I need to trust Ubuntu binary packages (because that make up 90% of the Trisquel packages), and many of those Ubuntu binaries are derived from Debian source packages. How to approach all of this? Last year I created the debdistrebuild project, and did top-50 popcon package rebuilds of Debian bullseye, bookworm, trixie, and Ubuntu noble and jammy, on a mix of amd64 and arm64. The amount of reproducibility was lower. Primarily the differences were caused by using different build inputs.

Last year I spent (too much) time creating a mirror of snapshot.debian.org, to be able to have older packages available for use as build inputs. I have two copies hosted at different datacentres for reliability and archival safety. At the time, snapshot.d.o had serious rate-limiting making it pretty unusable for massive rebuild usage or even basic downloads. Watching the multi-month download complete last year had a meditating effect. The completion of my snapshot download co-incided with me realizing something about the nature of rebuilding packages. Let me below give a recap of the idempotent rebuilds idea, because it motivate my work to build all of Debian from a GitLab pipeline.

One purpose for my effort is to be able to trust the binaries that I use on my laptop. I believe that without building binaries from source code, there is no practically feasible way to trust binaries. To trust any binary you receive, you can de-assemble the bits and audit the assembler instructions for the CPU you will execute it on. Doing that on a OS-wide level this is unpractical. A more practical approach is to audit the source code, and then confirm that the binary is 100% bit-by-bit identical to one that you can build yourself (from the same source) on your own trusted toolchain. This is similar to a reproducible build.

My initial goal with debdistrebuild was to get to 100% bit-by-bit identical rebuilds, and then I would have trustworthy binaries. Or so I thought. This also appears to be the goal of reproduce.debian.net. They want to reproduce the official Debian binaries. That is a worthy and important goal. They achieve this by building packages using the build inputs that were used to build the binaries. The build inputs are earlier versions of Debian packages (not necessarily from any public Debian release), archived at snapshot.debian.org.

I realized that these rebuilds would be not be sufficient for me: it doesn’t solve the problem of how to trust the toolchain. Let’s assume the reproduce.debian.net effort succeeds and is able to 100% bit-by-bit identically reproduce the official Debian binaries. Which appears to be within reach. To have trusted binaries we would “only” have to audit the source code for the latest version of the packages AND audit the tool chain used. There is no escaping from auditing all the source code — that’s what I think we all would prefer to focus on, to be able to improve upstream source code.

The trouble is about auditing the tool chain. With the Reproduce.debian.net approach, that is a recursive problem back to really ancient Debian packages, some of them which may no longer build or work, or even be legally distributable. Auditing all those old packages is a LARGER effort than auditing all current packages! Doing auditing of old packages is of less use to making contributions: those releases are old, and chances are any improvements have already been implemented and released. Or that improvements are no longer applicable because the projects evolved since the earlier version.

See where this is going now? I reached the conclusion that reproducing official binaries using the same build inputs is not what I’m interested in. I want to be able to build the binaries that I use from source using a toolchain that I can also build from source. And preferably that all of this is using latest version of all packages, so that I can contribute and send patches for them, to improve matters.

The toolchain that Reproduce.Debian.Net is using is not trustworthy unless all those ancient packages are audited or rebuilt bit-by-bit identically, and I don’t see any practical way forward to achieve that goal. Nor have I seen anyone working on that problem. It is possible to do, though, but I think there are simpler ways to achieve the same goal.

My approach to reach trusted binaries on my laptop appears to be a three-step effort:

- Encourage an idempotently rebuildable Debian archive, i.e., a Debian archive that can be 100% bit-by-bit identically rebuilt using Debian itself.

- Construct a smaller number of binary

*.debpackages based on Guix binaries that when used as build inputs (potentially iteratively) leads to 100% bit-by-bit identical packages as in step 1. - Encourage a freedom respecting distribution, similar to Trisquel, from this idempotently rebuildable Debian.

How to go about achieving this? Today’s Debian build architecture is something that lack transparency and end-user control. The build environment and signing keys are managed by, or influenced by, unidentified people following undocumented (or at least not public) security procedures, under unknown legal jurisdictions. I always wondered why none of the Debian-derivates have adopted a modern GitDevOps-style approach as a method to improve binary build transparency, maybe I missed some project?

If you want to contribute to some GitHub or GitLab project, you click the ‘Fork’ button and get a CI/CD pipeline running which rebuild artifacts for the project. This makes it easy for people to contribute, and you get good QA control because the entire chain up until its artifact release are produced and tested. At least in theory. Many projects are behind on this, but it seems like this is a useful goal for all projects. This is also liberating: all users are able to reproduce artifacts. There is no longer any magic involved in preparing release artifacts. As we’ve seen with many software supply-chain security incidents for the past years, where the “magic” is involved is a good place to introduce malicious code.

To allow me to continue with my experiment, I thought the simplest way forward was to setup a GitDevOps-centric and user-controllable way to build the entire Debian archive. Let me introduce the debdistbuild project.

Debdistbuild is a re-usable GitLab CI/CD pipeline, similar to the Salsa CI pipeline. It provide one “build” job definition and one “deploy” job definition. The pipeline can run on GitLab.org Shared Runners or you can set up your own runners, like my GitLab riscv64 runner setup. I have concerns about relying on GitLab (both as software and as a service), but my ideas are easy to transfer to some other GitDevSecOps setup such as Codeberg.org. Self-hosting GitLab, including self-hosted runners, is common today, and Debian rely increasingly on Salsa for this. All of the build infrastructure could be hosted on Salsa eventually.

The build job is simple. From within an official Debian container image build packages using dpkg-buildpackage essentially by invoking the following commands.

sed -i 's/ deb$/ deb deb-src/' /etc/apt/sources.list.d/*.sources

apt-get -o Acquire::Check-Valid-Until=false update

apt-get dist-upgrade -q -y

apt-get install -q -y --no-install-recommends build-essential fakeroot

env DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractive \

apt-get build-dep -y --only-source $PACKAGE=$VERSION

useradd -m build

DDB_BUILDDIR=/build/reproducible-path

chgrp build $DDB_BUILDDIR

chmod g+w $DDB_BUILDDIR

su build -c "apt-get source --only-source $PACKAGE=$VERSION" > ../$PACKAGE_$VERSION.build

cd $DDB_BUILDDIR

su build -c "dpkg-buildpackage"

cd ..

mkdir out

mv -v $(find $DDB_BUILDDIR -maxdepth 1 -type f) out/The deploy job is also simple. It commit artifacts to a Git project using Git-LFS to handle large objects, essentially something like this:

if ! grep -q '^pool/**' .gitattributes; then

git lfs track 'pool/**'

git add .gitattributes

git commit -m"Track pool/* with Git-LFS." .gitattributes

fi

POOLDIR=$(if test "$(echo "$PACKAGE" | cut -c1-3)" = "lib"; then C=4; else C=1; fi; echo "$DDB_PACKAGE" | cut -c1-$C)

mkdir -pv pool/main/$POOLDIR/

rm -rfv pool/main/$POOLDIR/$PACKAGE

mv -v out pool/main/$POOLDIR/$PACKAGE

git add pool

git commit -m"Add $PACKAGE." -m "$CI_JOB_URL" -m "$VERSION" -a

if test "${DDB_GIT_TOKEN:-}" = ""; then

echo "SKIP: Skipping git push due to missing DDB_GIT_TOKEN (see README)."

else

git push -o ci.skip

fiThat’s it! The actual implementation is a bit longer, but the major difference is for log and error handling.

You may review the source code of the base Debdistbuild pipeline definition, the base Debdistbuild script and the rc.d/-style scripts implementing the build.d/ process and the deploy.d/ commands.

There was one complication related to artifact size. GitLab.org job artifacts are limited to 1GB. Several packages in Debian produce artifacts larger than this. What to do? GitLab supports up to 5GB for files stored in its package registry, but this limit is too close for my comfort, having seen some multi-GB artifacts already. I made the build job optionally upload artifacts to a S3 bucket using SHA256 hashed file hierarchy. I’m using Hetzner Object Storage but there are many S3 providers around, including self-hosting options. This hierarchy is compatible with the Git-LFS .git/lfs/object/ hierarchy, and it is easy to setup a separate Git-LFS object URL to allow Git-LFS object downloads from the S3 bucket. In this mode, only Git-LFS stubs are pushed to the git repository. It should have no trouble handling the large number of files, since I have earlier experience with Apt mirrors in Git-LFS.

To speed up job execution, and to guarantee a stable build environment, instead of installing build-essential packages on every build job execution, I prepare some build container images. The project responsible for this is tentatively called stage-N-containers. Right now it create containers suitable for rolling builds of trixie on amd64, arm64, and riscv64, and a container intended for as use the stage-0 based on the 20250407 docker images of bookworm on amd64 and arm64 using the snapshot.d.o 20250407 archive. Or actually, I’m using snapshot-cloudflare.d.o because of download speed and reliability. I would have prefered to use my own snapshot mirror with Hetzner bandwidth, alas the Debian snapshot team have concerns about me publishing the list of (SHA1 hash) filenames publicly and I haven’t been bothered to set up non-public access.

Debdistbuild has built around 2.500 packages for bookworm on amd64 and bookworm on arm64. To confirm the generality of my approach, it also build trixie on amd64, trixie on arm64 and trixie on riscv64. The riscv64 builds are all on my own hosted runners. For amd64 and arm64 my own runners are only used for large packages where the GitLab.com shared runners run into the 3 hour time limit.

What’s next in this venture? Some ideas include:

- Optimize the stage-N build process by identifying the transitive closure of build dependencies from some initial set of packages.

- Create a build orchestrator that launches pipelines based on the previous list of packages, as necessary to fill the archive with necessary packages. Currently I’m using a basic /bin/sh

forloop aroundcurlto trigger GitLab CI/CD pipelines with names derived from https://popcon.debian.org/. - Create and publish a

dists/sub-directory, so that it is possible to use the newly built packages in the stage-1 build phase. - Produce diffoscope-style differences of built packages, both stage0 against official binaries and between stage0 and stage1.

- Create the stage-1 build containers and stage-1 archive.

- Review build failures. On amd64 and arm64 the list is small (below 10 out of ~5000 builds), but on riscv64 there is some icache-related problem that affects Java JVM that triggers build failures.

- Provide GitLab pipeline based builds of the Debian docker container images, cloud-images, debian-live CD and debian-installer ISO’s.

- Provide integration with Sigstore and Sigsum for signing of Debian binaries with transparency-safe properties.

- Implement a simple replacement for

dpkgandaptusing/bin/shfor use during bootstrapping when neither packaging tools are available.

What do you think?