The release notes for Trisquel 11.0 “Aramo” mention support for POWER and ARM architectures, however the download area only contains links for x86, and forum posts suggest there is a lack of instructions how to run Trisquel on non-x86.

Since the release of Trisquel 11 I have been busy migrating x86 machines from Debian to Trisquel. One would think that I would be finished after this time period, but re-installing and migrating machines is really time consuming, especially if you allow yourself to be distracted every time you notice something that Really Ought to be improved. Rabbit holes all the way down. One of my production machines is running Debian 11 “bullseye” on a Talos II Lite machine from Raptor Computing Systems, and migrating the virtual machines running on that host (including the VM that serves this blog) to a x86 machine running Trisquel felt unsatisfying to me. I want to migrate my computing towards hardware that harmonize with FSF’s Respects Your Freedom and not away from it. Here I had to chose between using the non-free software present in newer Debian or the non-free software implied by most x86 systems: not an easy chose. So I have ignored the dilemma for some time. After all, the machine was running Debian 11 “bullseye”, which was released before Debian started to require use of non-free software. With the end-of-life date for bullseye approaching, it seems that this isn’t a sustainable choice.

There is a report open about providing ppc64el ISOs that was created by Jason Self shortly after the release, but for many months nothing happened. About a month ago, Luis Guzmán mentioned an initial ISO build and I started testing it. The setup has worked well for a month, and with this post I want to contribute instructions how to get it up and running since this is still missing.

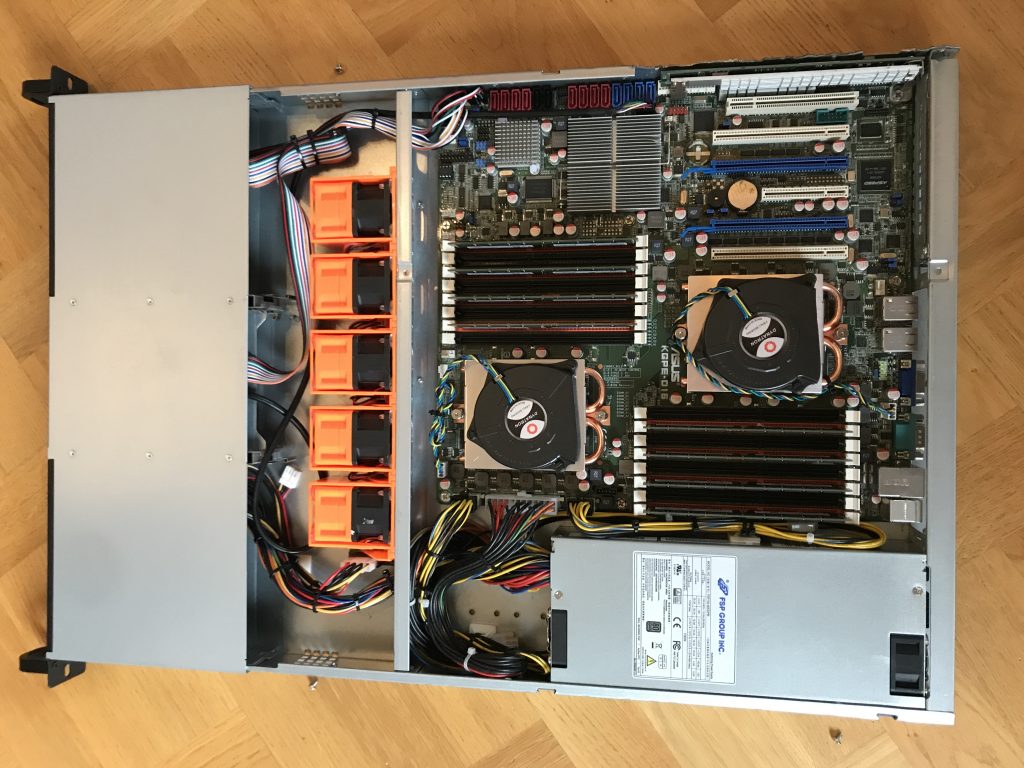

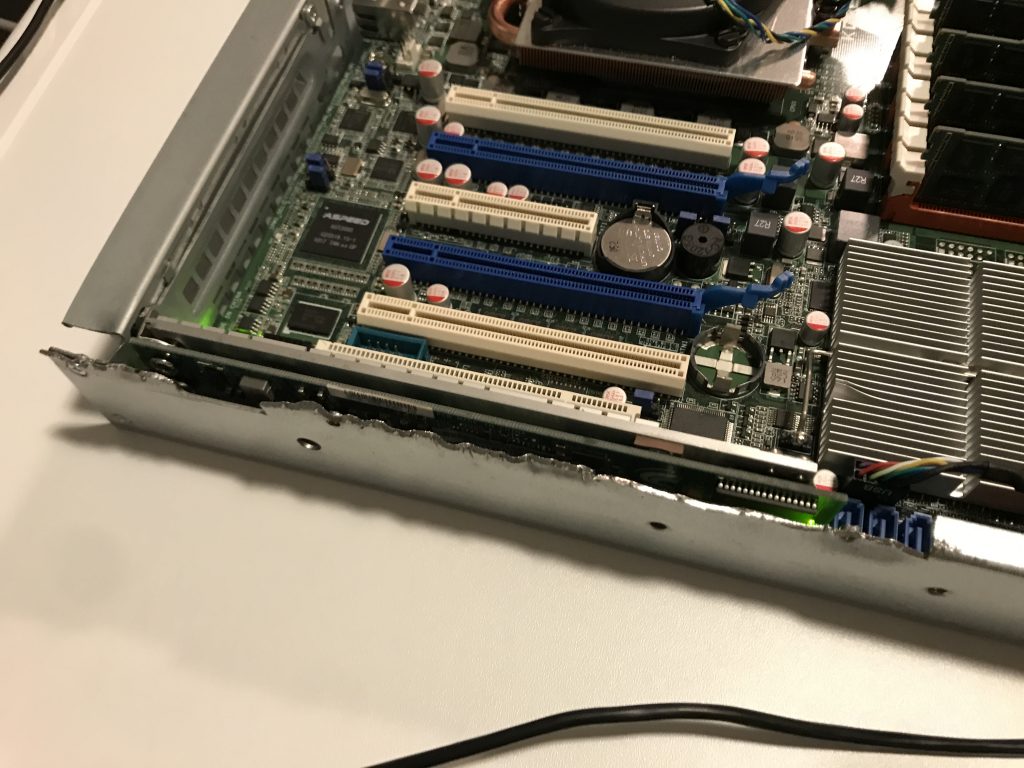

The setup of my soon-to-be new production machine:

- Talos II Lite

- POWER9 18-core v2 CPU

- Inter-Tech 4U-4410 rack case with ASPOWER power supply

- 8x32GB DDR4-2666 ECC RDIMM

- HighPoint SSD7505 (the Rocket 1504 or 1204 would be a more cost-effective choice, but I re-used a component I had laying around)

- PERC H700 aka LSI MegaRAID 2108 SAS/SATA (also found laying around)

- 2x1TB NVMe

- 3x18TB disks

According to the notes in issue 14 the ISO image is available at https://builds.trisquel.org/debian-installer-images/ and the following commands download, integrity check and write it to a USB stick:

wget -q https://builds.trisquel.org/debian-installer-images/debian-installer-images_20210731+deb11u8+11.0trisquel14_ppc64el.tar.gz

tar xfa debian-installer-images_20210731+deb11u8+11.0trisquel14_ppc64el.tar.gz ./installer-ppc64el/20210731+deb11u8+11/images/netboot/mini.iso

echo '6df8f45fbc0e7a5fadf039e9de7fa2dc57a4d466e95d65f2eabeec80577631b7 ./installer-ppc64el/20210731+deb11u8+11/images/netboot/mini.iso' | sha256sum -c

sudo wipefs -a /dev/sdX

sudo dd if=./installer-ppc64el/20210731+deb11u8+11/images/netboot/mini.iso of=/dev/sdX conv=sync status=progressSadly, no hash checksums or OpenPGP signatures are published.

Power off your device, insert the USB stick, and power it up, and you see a Petitboot menu offering to boot from the USB stick. For some reason, the "Expert Install" was the default in the menu, and instead I select "Default Install" for the regular experience. For this post, I will ignore BMC/IPMI, as interacting with it is not necessary. Make sure to not connect the BMC/IPMI ethernet port unless you are willing to enter that dungeon. The VGA console works fine with a normal USB keyboard, and you can chose to use only the second enP4p1s0f1 network card in the network card selection menu.

If you are familiar with Debian netinst ISO’s, the installation is straight-forward. I complicate the setup by partitioning two RAID1 partitions on the two NVMe sticks, one RAID1 for a 75GB ext4 root filesystem (discard,noatime) and one RAID1 for a 900GB LVM volume group for virtual machines, and two 20GB swap partitions on each of the NVMe sticks (to silence a warning about lack of swap, I’m not sure swap is still a good idea?). The 3x18TB disks use DM-integrity with RAID1 however the installer does not support DM-integrity so I had to create it after the installation.

There are two additional matters worth mentioning:

- Selecting the apt mirror does not have the list of well-known Trisquel mirrors which the x86 installer offers. Instead I have to input the archive mirror manually, and fortunately the

archive.trisquel.orghostname and path values are available as defaults, so I just press enter and fix this after the installation has finished. You may want to have the hostname/path of your local mirror handy, to speed things up. - The installer asks me which kernel to use, which the x86 installer does not do. I believe older Trisquel/Ubuntu installers asked this question, but that it was gone in aramo on x86. I select the default “

linux-image-generic” which gives me a predictable 5.15 Linux-libre kernel, although you may want to chose “linux-image-generic-hwe-11.0” for a more recent 6.2 Linux-libre kernel. Maybe this is intentional debinst-behaviour for non-x86 platforms?

I have re-installed the machine a couple of times, and have now finished installing the production setup. I haven’t ran into any serious issues, and the system has been stable. Time to wrap up, and celebrate that I now run an operating system aligned with the Free System Distribution Guidelines on hardware that aligns with Respects Your Freedom — Happy Hacking indeed!