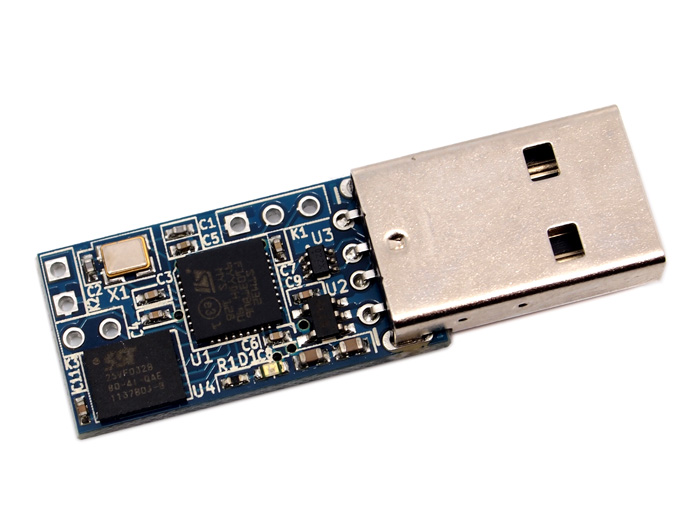

I installed Debian 9.0 “Stretch” on my Lenovo X201 laptop today. Installation went smooth, as usual. GnuPG/SSH with an OpenPGP smartcard — I use a YubiKey NEO — does not work out of the box with GNOME though. I wrote about how to fix OpenPGP smartcards under GNOME with Debian 8.0 “Jessie” earlier, and I thought I’d do a similar blog post for Debian 9.0 “Stretch”. The situation is slightly different than before (e.g., GnuPG works better but SSH doesn’t) so there is some progress. May I hope that Debian 10.0 “Buster” gets this right? Pointers to which package in Debian should have a bug report tracking this issue is welcome (or a pointer to an existing bug report).

After first login, I attempt to use gpg --card-status to check if GnuPG can talk to the smartcard.

jas@latte:~$ gpg --card-status

gpg: error getting version from 'scdaemon': No SmartCard daemon

gpg: OpenPGP card not available: No SmartCard daemon

jas@latte:~$

This fails because scdaemon is not installed. Isn’t a smartcard common enough so that this should be installed by default on a GNOME Desktop Debian installation? Anyway, install it as follows.

root@latte:~# apt-get install scdaemon

Then try again.

jas@latte:~$ gpg --card-status

gpg: selecting openpgp failed: No such device

gpg: OpenPGP card not available: No such device

jas@latte:~$

I believe scdaemon here attempts to use its internal CCID implementation, and I do not know why it does not work. At this point I often recall that want pcscd installed since I work with smartcards in general.

root@latte:~# apt-get install pcscd

Now gpg --card-status works!

jas@latte:~$ gpg --card-status

Reader ...........: Yubico Yubikey NEO CCID 00 00

Application ID ...: D2760001240102000006017403230000

Version ..........: 2.0

Manufacturer .....: Yubico

Serial number ....: 01740323

Name of cardholder: Simon Josefsson

Language prefs ...: sv

Sex ..............: male

URL of public key : https://josefsson.org/54265e8c.txt

Login data .......: jas

Signature PIN ....: not forced

Key attributes ...: rsa2048 rsa2048 rsa2048

Max. PIN lengths .: 127 127 127

PIN retry counter : 3 3 3

Signature counter : 8358

Signature key ....: 9941 5CE1 905D 0E55 A9F8 8026 860B 7FBB 32F8 119D

created ....: 2014-06-22 19:19:04

Encryption key....: DC9F 9B7D 8831 692A A852 D95B 9535 162A 78EC D86B

created ....: 2014-06-22 19:19:20

Authentication key: 2E08 856F 4B22 2148 A40A 3E45 AF66 08D7 36BA 8F9B

created ....: 2014-06-22 19:19:41

General key info..: sub rsa2048/860B7FBB32F8119D 2014-06-22 Simon Josefsson

sec# rsa3744/0664A76954265E8C created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04

ssb> rsa2048/860B7FBB32F8119D created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04

card-no: 0006 01740323

ssb> rsa2048/9535162A78ECD86B created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04

card-no: 0006 01740323

ssb> rsa2048/AF6608D736BA8F9B created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04

card-no: 0006 01740323

jas@latte:~$

Using the key will not work though.

jas@latte:~$ echo foo|gpg -a --sign

gpg: no default secret key: No secret key

gpg: signing failed: No secret key

jas@latte:~$

This is because the public key and the secret key stub are not available.

jas@latte:~$ gpg --list-keys

jas@latte:~$ gpg --list-secret-keys

jas@latte:~$

You need to import the key for this to work. I have some vague memory that gpg --card-status was supposed to do this, but I may be wrong.

jas@latte:~$ gpg --recv-keys 9AA9BDB11BB1B99A21285A330664A76954265E8C

gpg: failed to start the dirmngr '/usr/bin/dirmngr': No such file or directory

gpg: connecting dirmngr at '/run/user/1000/gnupg/S.dirmngr' failed: No such file or directory

gpg: keyserver receive failed: No dirmngr

jas@latte:~$

Surprisingly, dirmngr is also not shipped by default so it has to be installed manually.

root@latte:~# apt-get install dirmngr

Below I proceed to trust the clouds to find my key.

jas@latte:~$ gpg --recv-keys 9AA9BDB11BB1B99A21285A330664A76954265E8C

gpg: key 0664A76954265E8C: public key "Simon Josefsson " imported

gpg: no ultimately trusted keys found

gpg: Total number processed: 1

gpg: imported: 1

jas@latte:~$

Now the public key and the secret key stub are available locally.

jas@latte:~$ gpg --list-keys

/home/jas/.gnupg/pubring.kbx

----------------------------

pub rsa3744 2014-06-22 [SC] [expires: 2017-09-04]

9AA9BDB11BB1B99A21285A330664A76954265E8C

uid [ unknown] Simon Josefsson

uid [ unknown] Simon Josefsson

sub rsa2048 2014-06-22 [S] [expires: 2017-09-04]

sub rsa2048 2014-06-22 [E] [expires: 2017-09-04]

sub rsa2048 2014-06-22 [A] [expires: 2017-09-04]

jas@latte:~$ gpg --list-secret-keys

/home/jas/.gnupg/pubring.kbx

----------------------------

sec# rsa3744 2014-06-22 [SC] [expires: 2017-09-04]

9AA9BDB11BB1B99A21285A330664A76954265E8C

uid [ unknown] Simon Josefsson

uid [ unknown] Simon Josefsson

ssb> rsa2048 2014-06-22 [S] [expires: 2017-09-04]

ssb> rsa2048 2014-06-22 [E] [expires: 2017-09-04]

ssb> rsa2048 2014-06-22 [A] [expires: 2017-09-04]

jas@latte:~$

I am now able to sign data with the smartcard, yay!

jas@latte:~$ echo foo|gpg -a --sign

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE-----

owGbwMvMwMHYxl2/2+iH4FzG01xJDJFu3+XT8vO5OhmNWRgYORhkxRRZZjrGPJwQ

yxe68keDGkwxKxNIJQMXpwBMRJGd/a98NMPJQt6jaoyO9yUVlmS7s7qm+Kjwr53G

uq9wQ+z+/kOdk9w4Q39+SMvc+mEV72kuH9WaW9bVqj80jN77hUbfTn5mffu2/aVL

h/IneTfaOQaukHij/P8A0//Phg/maWbONUjjySrl+a3tP8ll6/oeCd8g/aeTlH79

i0naanjW4bjv9wnvGuN+LPHLmhUc2zvZdyK3xttN/roHvsdX3f53yTAxeInvXZmd

x7W0/hVPX33Y4nT877T/ak4L057IBSavaPVcf4yhglVI8XuGgaTP666Wuslbliy4

5W5eLasbd33Xd/W0hTINznuz0kJ4r1bLHZW9fvjLduMPq5rS2co9tvW8nX9rhZ/D

zycu/QA=

=I8rt

-----END PGP MESSAGE-----

jas@latte:~$

Encrypting to myself will not work smoothly though.

jas@latte:~$ echo foo|gpg -a --encrypt -r simon@josefsson.org

gpg: 9535162A78ECD86B: There is no assurance this key belongs to the named user

sub rsa2048/9535162A78ECD86B 2014-06-22 Simon Josefsson

Primary key fingerprint: 9AA9 BDB1 1BB1 B99A 2128 5A33 0664 A769 5426 5E8C

Subkey fingerprint: DC9F 9B7D 8831 692A A852 D95B 9535 162A 78EC D86B

It is NOT certain that the key belongs to the person named

in the user ID. If you *really* know what you are doing,

you may answer the next question with yes.

Use this key anyway? (y/N)

gpg: signal Interrupt caught ... exiting

jas@latte:~$

The reason is that the newly imported key has unknown trust settings. I update the trust settings on my key to fix this, and encrypting now works without a prompt.

jas@latte:~$ gpg --edit-key 9AA9BDB11BB1B99A21285A330664A76954265E8C

gpg (GnuPG) 2.1.18; Copyright (C) 2017 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law.

Secret key is available.

pub rsa3744/0664A76954265E8C

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: SC

trust: unknown validity: unknown

ssb rsa2048/860B7FBB32F8119D

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: S

card-no: 0006 01740323

ssb rsa2048/9535162A78ECD86B

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: E

card-no: 0006 01740323

ssb rsa2048/AF6608D736BA8F9B

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: A

card-no: 0006 01740323

[ unknown] (1). Simon Josefsson

[ unknown] (2) Simon Josefsson

gpg> trust

pub rsa3744/0664A76954265E8C

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: SC

trust: unknown validity: unknown

ssb rsa2048/860B7FBB32F8119D

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: S

card-no: 0006 01740323

ssb rsa2048/9535162A78ECD86B

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: E

card-no: 0006 01740323

ssb rsa2048/AF6608D736BA8F9B

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: A

card-no: 0006 01740323

[ unknown] (1). Simon Josefsson

[ unknown] (2) Simon Josefsson

Please decide how far you trust this user to correctly verify other users' keys

(by looking at passports, checking fingerprints from different sources, etc.)

1 = I don't know or won't say

2 = I do NOT trust

3 = I trust marginally

4 = I trust fully

5 = I trust ultimately

m = back to the main menu

Your decision? 5

Do you really want to set this key to ultimate trust? (y/N) y

pub rsa3744/0664A76954265E8C

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: SC

trust: ultimate validity: unknown

ssb rsa2048/860B7FBB32F8119D

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: S

card-no: 0006 01740323

ssb rsa2048/9535162A78ECD86B

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: E

card-no: 0006 01740323

ssb rsa2048/AF6608D736BA8F9B

created: 2014-06-22 expires: 2017-09-04 usage: A

card-no: 0006 01740323

[ unknown] (1). Simon Josefsson

[ unknown] (2) Simon Josefsson

Please note that the shown key validity is not necessarily correct

unless you restart the program.

gpg> quit

jas@latte:~$ echo foo|gpg -a --encrypt -r simon@josefsson.org

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE-----

hQEMA5U1Fip47NhrAQgArTvAykj/YRhWVuXb6nzeEigtlvKFSmGHmbNkJgF5+r1/

/hWENR72wsb1L0ROaLIjM3iIwNmyBURMiG+xV8ZE03VNbJdORW+S0fO6Ck4FaIj8

iL2/CXyp1obq1xCeYjdPf2nrz/P2Evu69s1K2/0i9y2KOK+0+u9fEGdAge8Gup6y

PWFDFkNj2YiVa383BqJ+kV51tfquw+T4y5MfVWBoHlhm46GgwjIxXiI+uBa655IM

EgwrONcZTbAWSV4/ShhR9ug9AzGIJgpu9x8k2i+yKcBsgAh/+d8v7joUaPRZlGIr

kim217hpA3/VLIFxTTkkm/BO1KWBlblxvVaL3RZDDNI5AVp0SASswqBqT3W5ew+K

nKdQ6UTMhEFe8xddsLjkI9+AzHfiuDCDxnxNgI1haI6obp9eeouGXUKG

=s6kt

-----END PGP MESSAGE-----

jas@latte:~$

So everything is fine, isn’t it? Alas, not quite.

jas@latte:~$ ssh-add -L

The agent has no identities.

jas@latte:~$

Tracking this down, I now realize that GNOME’s keyring is used for SSH but GnuPG’s gpg-agent is used for GnuPG. GnuPG uses the environment variable GPG_AGENT_INFO to connect to an agent, and SSH uses the SSH_AUTH_SOCK environment variable to find its agent. The filenames used below leak the knowledge that gpg-agent is used for GnuPG but GNOME keyring is used for SSH.

jas@latte:~$ echo $GPG_AGENT_INFO

/run/user/1000/gnupg/S.gpg-agent:0:1

jas@latte:~$ echo $SSH_AUTH_SOCK

/run/user/1000/keyring/ssh

jas@latte:~$

Here the same recipe as in my previous blog post works. This time GNOME keyring only has to be disabled for SSH. Disabling GNOME keyring is not sufficient, you also need gpg-agent to start with enable-ssh-support. The simplest way to achieve that is to add a line in ~/.gnupg/gpg-agent.conf as follows. When you login, the script /etc/X11/Xsession.d/90gpg-agent will set the environment variables GPG_AGENT_INFO and SSH_AUTH_SOCK. The latter variable is only set if enable-ssh-support is mentioned in the gpg-agent configuration.

jas@latte:~$ mkdir ~/.config/autostart

jas@latte:~$ cp /etc/xdg/autostart/gnome-keyring-ssh.desktop ~/.config/autostart/

jas@latte:~$ echo 'Hidden=true' >> ~/.config/autostart/gnome-keyring-ssh.desktop

jas@latte:~$ echo enable-ssh-support >> ~/.gnupg/gpg-agent.conf

jas@latte:~$

Log out from GNOME and log in again. Now you should see ssh-add -L working.

jas@latte:~$ ssh-add -L

ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQDFP+UOTZJ+OXydpmbKmdGOVoJJz8se7lMs139T+TNLryk3EEWF+GqbB4VgzxzrGjwAMSjeQkAMb7Sbn+VpbJf1JDPFBHoYJQmg6CX4kFRaGZT6DHbYjgia59WkdkEYTtB7KPkbFWleo/RZT2u3f8eTedrP7dhSX0azN0lDuu/wBrwedzSV+AiPr10rQaCTp1V8sKbhz5ryOXHQW0Gcps6JraRzMW+ooKFX3lPq0pZa7qL9F6sE4sDFvtOdbRJoZS1b88aZrENGx8KSrcMzARq9UBn1plsEG4/3BRv/BgHHaF+d97by52R0VVyIXpLlkdp1Uk4D9cQptgaH4UAyI1vr cardno:000601740323

jas@latte:~$

Topics for further discussion or research include 1) whether scdaemon, dirmngr and/or pcscd should be pre-installed on Debian desktop systems; 2) whether gpg --card-status should attempt to import the public key and secret key stub automatically; 3) why GNOME keyring is used by default for SSH rather than gpg-agent; 4) whether GNOME keyring should support smartcards, or if it is better to always use gpg-agent for GnuPG/SSH, 5) if something could/should be done to automatically infer the trust setting for a secret key.

Enjoy!